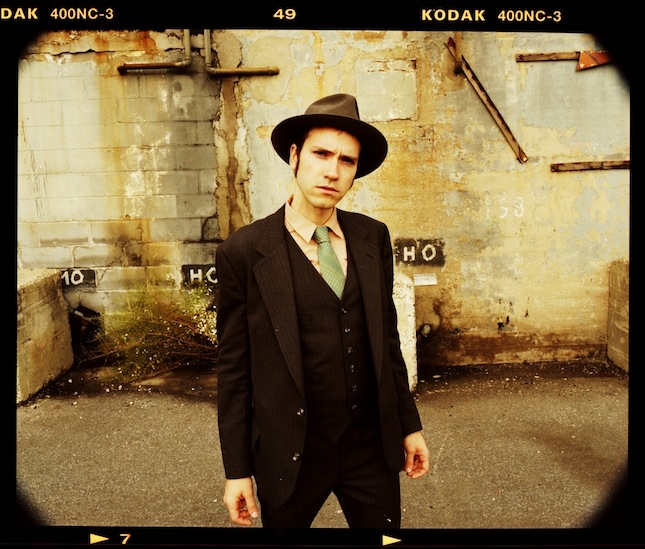

Jeremiah Lockwood on the Mystical Lights of the Guitar

-

There is one more night of Hanukkah and then one more night beyond that of the Tikva Records store in San Francisco..

Both will be hosted by Jeremiah Lockwood, the New York musician best known for his work with the band the Sway Machinery. The nights, together titled the Mystical Lights of the Guitar, will put him together with special guests. On Tuesday, December 27, it will be Greg Ashley (of Gris Gris) and Lewis Pesacov (of Fool’s Gold, who performed at Tikva on December 7), and on Wednesday, December 28, it will be Luther Dickinson (Black Crowes, North Mississippi Allstars) and Ethan Miller (Comets On Fire, Howlin Rain).

Lockwood, speaking from home in advance of the shows. talked about creating rock music out of the cantorial tradition, about the inherent Jewish-ness of ethnomusicology, and about what we can expect from his pair of concerts.

Tikva Records: Tell us a little bit about your relationship with the musicians you’ll be performing with.

Jeremiah Lockwood: Having a chance to play with Luther and Ethan will be a real thrill. I am really looking forward to it. I met Ethan when we did the second Mazeltov Mis Amigos shows — he was on that, as well. We didn’t really play together, but we were hanging out. I met Luther a long time ago, when I was a teenager still, when I recorded on a friend’s record, the singer-songwriter Kieran McGee. I was playing with him and we recorded at Sun Studio, which was a wonderful experience, and Luther and his brother, Cody, also played on the record. We were hanging out with them. That was fantastic, a deep wealth of music from that part of America. At that age, that was my primary focus, studying old blues records.

Tikva: One way of understanding the Tikva Records project, and more broadly the Idelsohn Society, is that Jews, having been early and great collectors of blues and jazz and bluegrass, are now turning that enterprise on their own recorded culture.

Lockwood: I think Jewish people have always been on the the innovation end of ethnomusicology. I mean, Jews in a way invented it, kind of literally: Curt Sachs, the pioneering German-born ethnomusicologist, was a Jew. And Jews were using similar techniques to use Western musical notation and ideas about how to explain music. They were using that to explain their own music, using Western notation to transcribe Jewish music from an earlier time. This idea of taking the technology of the host culture or the present moment and using it to self-analyze is kind of deeply embedded in Jewish thinking.

Tikva: Do you have a sense of how the two Tikva Records shows will differ?

Lockwood: The first night I am going to do a solo set, and maybe some stuff with Lew from Fool’s Gold. The second night is going to be a round robin. I’ll play a song, then we’ll play a song together, more of a psychedelic folk jam.

Tikva: So you’ll be exploring the outer realms?

Lockwood: We’ll be exploring realms of consciousness, certainly.

Tikva: That will be good to do with all the candles around. Is there a Jewish part of the psychedelic experience you’d could touch on here?

Lockwood: My music is connected to Jewish cantorial music, spiritual music — my band Sway Machinery does a lot of interpretations and covers of old 1920s and ‘30s records, old cantorial music, and so I am going to do some pieces that are kind of from that realm of thought, and we’re working on some pieces — Ethan and I — including a Jewish piece, Hanukkah-themed, that’s going to be a psychedelic experience, absolutely.

Tikva: The audiences for the Tikva Records shows thus far have drawn, it seems, from two broadly defined realms: from music fans, and people coming for the Jewish experience.

Lockwood: That’s sort of normal for me. The Sway Machinery has done a bunch of Jewish-themed events in the past. One of the best things we’ve done is this concert we did on the night of Rosh Hashanah, and it was like taking old Rosh Hashanah liturgy as performed by great cantors of the early 20th century, and then reinterpreting and turning it into this … like, a rock concert, basically. People there, I would say, were maybe half music lovers and half coming to it as an expression of their Jewish roots, their version of going to services for Rosh Hashanah. It’s good to cover all the bases.

Tikva: Was anyone from the latter audience taken aback?

Lockwood: From the Jewish world? People who aren’t going to like it don’t come, obviously: It’s a show with electric guitars on a holiday. It’s not halokhe — people who don’t want that won’t come.

Tikva: What is your personal Jewish upbringing?

Lockwood: I didn’t really grow up religious. My family was secular. The funny thing is, my grandfather was a cantor, and my uncle was a cantor. My grandfather managed to avoid being occupied with issues of identity simply through the charisma with which he expressed his Jewishness and his Americanness. That was enough to sustain the family in the illusion that everything was OK.

Tikva: When you say everything is OK, you mean…

Lockwood: It was a manic century and a half. There had been a certain stasis, religious identity being the primary way of begin a Jew, and that then interacted with other modes of living: secular humanism, being an artist, being an intellectual. These are spheres of spiritual intellectual expression that run parallel to the more ancient mode.

Tikva: When you talk about your grandfather’s charisma, you mean that he walked through life proudly, but that in contrast a later generation maybe hid a little?

Lockwood: Yeah, hiding is a big part of the way people deal with the discomfort of being both of a subculture and also alienated from it. There’s a lot of hiding from both from one’s family — though not for me so much — and expressing the extent to which they were no longer observing, but also someone who is ill at ease with themselves.

Tikva: That’s a nice way to put it, in that it is about something that while perhaps endemic to the Jewish experience isn’t solely part of the Jewish experience — it’s something that people who come to the Tikva Records shows for the cultural aspect may themselves experience in their own lives.

Lockwood: The culture is the great wealth of why it is interesting, why we need to look at it. Stories, music — those are things we cannot do without. You can’t exist without your stories, and we try to find ways to express those stories that are true, and that come from a sense of urgency, of compulsion.

Check out the Tikva Records calendar for more information about the two events.